Cognitive Assessments are often used in the field of HR. Where do they come from? What do they measure and why are they valuable? All of that and much more, we will answer. Choose the topic that interests you the most from the topics below.

Interest in Measuring the Human Intellect

Interest in the capability of understanding and measuring the human intellect has grown steadily since the launch of the first intelligence test in 1905. Today the practice of using tests to highlight skills at schools and other institutes of education is quite widespread. Aptitude tests are commonplace in the corporate sector, while the combined aptitude/ability test is increasingly becoming a permanent feature of recruiting and human resources development procedures.

Even though the term intelligence in our day is broadly defined, the essence of intelligence, swift and competent problem solving, remains central to our ability to study and work. This is the sum and substance on which ACE and CORE focuses. This article deals with the history and research behind ability tests.

Philosophy to Empiricism

Studies of disparity in intellectual ability and potential came into focus in earnest in the mid-nineteenth century, when interest in differential psychology (the study of individual difference in behaviour) was gathering pace. Until that point the philosophical approach prevailed when issues of mental ability and individual difference were discussed. The philosophical approach has its roots inantiquity when the theories of Plato and Aristotle held sway. As far back as 2,700 years ago, Homer remarked in the Odyssey (about 700 BC) that one man may make a poor physical impression but speak in an articulate and persuasive way, another man may be handsome but lack the ability to communicate well with others.

Plato (427-347 BC) isolated the body from the mind (soul) in his philosophical writings. Although the words intelligence or intellect do not appear in his writings, he based his deliberations on that which we today would call intellectual or mental ability. He compared the human mind to a lump of wax on which impressions can be made of the world we observe around us, much in the same way as a plaster cast is made. Plato claimed that “impressions” were stored in the wax as casts. The lump of wax can vary in ‘hardness’, ‘moistness’ and ‘purity’. If the wax is pure, clear, and sufficiently deep, the mind will easily retain data and, at the same time, avoid creating confusion. The mind will only think ‘things’ that are true. Because the impressions in the wax are clear, they will be distributed quickly into their proper place in the lump of wax. If the wax is muddy and unclear or very soft or very hard, defects will appear in the intellect. People with soft wax learn quickly but forget just as fast. People with hard wax are slow learners but, conversely, retain what they have learned. People whose wax is uneven cannot but have unclear impressions. The same applies to those with hard wax, in that they are incapable of depth of thought. (Sternberg, 2000).

Aristotle (384-322 BC) came closer to our classification/understanding of the intellect. He maintained that mental ability, like thinking, the acquisition of knowledge and reasoning, rely on memory and feelings. He was the first to attribute to the psyche cognitive functions and emotions (Jensen, 1998).

In the mid-nineteenth century Francis Galton (1822-1911) was the first to conduct empirical studies of mental ability and individual difference. Unlike the philosophical approach, empirical studies are characterised by the systematic gathering of data, objective measurements, and experiments. Galton was fascinated with measuring and counting everything. Among his achievements was the development of a method to measure the degree to which a lecturer bored his audience. By measuring and calculating the number of coughs, sniffles, feet movements and the way in which the audience held their heads, he was able to assess how boring the lecture had been.

To compute the vast amount of data he had gathered from his innumerable studies, Galton developed a variety of statistical calculation methods, some of which are still in use today. Galton was and still is acknowledged as a scientist within many disciplines, including genetics, statistics, and psychology. With respect to mental ability and individual difference he was particularly taken up by the idea of hereditary genius. Galton’s conclusion was that people’s intelligence varied, and that an individual’s level of intelligence is largely hereditary. Since then, studies have concentrated on the development of theories and methods by which to understand and expose individual difference.

Galton seldom referred to the term intelligence and never developed any formal definition. His idea was that the better and more sensitive a person’s senses were, the more intelligent he or she would be. To measure this Galton used sensory discrimination and reaction-time tests. His sensory discrimination test measured the difference, (however little), a person could identify, when presented with almost identical sensory impressions. For instance, the difference between two almost equally long lines or two almost equally applied pressures to the hand. Sensory discrimination and reaction-time was, at the time, not considered particularly worthwhile in revealing individual difference.

With the first theories on individual difference came the ambition to devise methods by which to measure and predict future behaviour and success. The French psychologist Alfred Binet (1857-1911) believed intelligence could not be assessed by means of simple physiological sensory measurements.

Complicated tasks, he argued, were needed to assess complicated mental abilities. In 1904 the French government hired Binet and his colleague Theodor Simon to devise a method by which to measure a child’s preparedness for school. In 1905 Binet and Simon published the first IQ test. The test consisted in part of a list of questions to test the child’s vocabulary, understanding of numbers and logical associations, judgement, and so on. The test was standardised to equate with ‘the normal’ child. The test result was given as the child’s ‘mental age’. So, a seven-year-old who could solve assignments set for a four-year old had the mental age of four. Many people associate the term IQ (Intelligence Quotient) with Binet, although it was in fact his German colleague William Stern who coined the term in 1912.

With the arrival of the first intelligence test, intelligence research found its own momentum. By the onset of World War I, a need had arisen to select recruits and place them on various courses. Roughly 1,750,000 people were IQ tested. Candidates’ results were computed relative to the results of other candidates. Essentially the same methods are used in IQ tests today.

Today intelligence theories abound. Below we give a short introduction to some of the more established theories on and definitions of intelligence.

The G-Factor

Charles Spearman (1863-1945), a British psychologist, was fascinated by Galton’s theory on individual difference in mental ability and the reasons behind it. At the beginning of the twentieth century Spearman developed a statistical computation method to reduce the complexity of processing large quantities of data. This he termed factor analysis. With the aid of factor analysis Spearman discovered correlation between the results people obtained on different types of tests. If a person scores, for instance, above average in solving mathematical problems all things being equal, it followed that the same individual would be above average in executing written assignments, as well. What he had in fact discovered was general correlation between performance levels on different types of tests. Spearman attributed this phenomenon to an underlying factor: the g-Factor, (with g for general intelligence). According to Spearman the g-Factor is the general mental ability required to perform any type of task which demands mental ability (e.g., reading, understanding, and remembering). Figuratively this can be expressed as a mental foundation, or base: the higher the g-Factor, the more solid the base. Following on from this: the more solid the base, the stronger the abilities which can be built upon it. As the g-Factor rises, so too the person’s competence to acquire and thereafter perform any type of skill.

G is not the only factor that determines an individual’s performance in each context. Spearman discovered that in tests a candidate’s performance would vary commensurate with separate sub-tests. Spearman termed this the s Factor (with s for specific intelligence). Some people are better at arithmetic, others at writing, depending upon individual ability within the various disciplines. Of particular interest, however, was a closer look at the g-Factor, as this apparently had a bearing on a person’s performance across the spectrum of intellectual/mental challenges. With respect to job performance, the g-Factor is the universal ability to solve problems not necessarily interconnected with the particular nature of the problem.

Based on his studies, Spearman reached the conclusion that a special test obliging the candidate to detect and understand relations and correlations and consequently reason out a solution, was the best method of measuring a person’s g-level. The results manifest not only much about the candidate’s fitness to take the test, but also his/her ability to cope with a range of mental challenges, for instance, in his/her day-to-day job functions.

Fluid and crystallised Intelligence

The British psychologist, Raymond B. Cattell (1905-1992), ranked intelligence into what he termed Fluid Intelligence and Crystallised Intelligence. This widely acknowledged theory provides an excellent picture of the difference between mental potential and experience. In early intelligence tests this distinction was often lacking.

Fluid Intelligence is, according to Cattell, primarily biologically determined, and relates to our problem solving and reasoning capabilities, independent of earlier experience or learning. A test to assess logical reasoning ability will typically correlate high with fluid intelligence. According to Cattell, fluid intelligence declines with age.

Crystallised intelligence, conversely, is more directly contingent upon experience and learning. Unlike fluid intelligence, crystallised intelligence, according to Cattell, increases with age.

Cattell spent a deal of time producing what he termed a culture-free intelligence test, or a pure test of fluid intelligence, where a person’s earlier experience and abilities (culture) have no impact. It was later acknowledged that it is almost impossible to design such a test. But Cattell’s work does indicate how important it is to differentiate between experience and potential when testing intelligence.

Nature vs Nurture

Is intelligence hereditary - biologically speaking? Or is intelligence determined by upbringing?

These questions dominated the intelligence debate for most of the twentieth century. Francis Galton pioneered research in correlation between intelligence and genes. Galton was the first to study twins. His methods have supplied crucial arguments to the nature versus nurture debate. Looked at with contemporary eyes, however, Galton’s methods would seem particularly rough and ready. He confined his studies to individual families and made no distinction between fraternal and identical twins. His conclusion that intelligence is genetic is also thought to be built upon a rather shaky research foundation. More extensive studies of twins were conducted up until the 1970s. These typically measured the intelligence of twins and their parents when the biological parents raised one twin and adoptive parents the other. IQ differences between fraternal and identical twins were also a subject of study in this period. The twins’ IQ was then compared with that of their parents and adoptive parents, respectively. Many the results suggest that intelligence is to a large extent hereditary.

Kamin (1974) questioned the widely acknowledged assumption that intelligence is hereditary. Kamin pointed to several research errors and deficiencies, including a major twin study conducted by the renowned psychologist and statistician Cyril Burt. The results of Burt’s study appeared strikingly similar, although he studied different groups of twins. Doubts remain as to whether or not, and to what extent, Burt wilfully manipulated data. But the outcome of this condemnation, clearly, was massive uncertainty for decades afterwards on the extent to which intelligence is hereditary.

Today, there is broad consensus that intelligence is partly genetically determined. Correlation between adopted twins and their biological parents has in studies been shown to be as high as between biological parents and the children raised by the parents themselves (Scarr and Weinberg, 1983 in Sternberg, 2000).

It is also apparent, however, that genetics, understood as the genes with which we are born, is an inadequate explanation of a person’s intelligence. For further discussion on this topic refer see the list of references (e.g., Grigorenko in Sternberg, 2000).

Multiple Intelligences?

Another popular approach is Howard Gardner’s (1943 - ) theory of multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1983 & 1997). Gardner’s theory defines a broader term for intelligence that embraces abilities other than those directly related to schooling and education (e.g., Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence, Musical Intelligence, Interpersonal Intelligence, and so on). Central to his theory is that the word intelligence is only a term that describes ability to solve problems/perform tasks and develop products within many fields. Specific mental processes are linked to each of these fields expressed, to a greater or lesser degree, by the individual. These specific mental processes are activated when the individual receives or is obliged to take a stand on a definitive task type, such as written material. To work on written material a person must command an understanding of language and its subtleties, be able to summarise the material read, and later recap what has been read clearly for others. Linguistic Intelligence is but one of seven types of intelligence identified by Gardner. Gardner has since identified at least two other intelligence types. His revised theory identifies nine types of intelligence in all. See Gardner’s publications (1983, 1997) for a more in-depth look at his intelligence theories.

We bring our linguistic intelligence into play in everyday scenarios, using language for specific purposes, e.g., to convince others, to develop and support our memories, to pass on information (at lectures, courses), and to reflect (to interpret something that has been said).

According to Gardner these various types of intelligence are subject to periods of development, for which reason stimulation of all our intelligences is important to human development. The various intelligences are not expressed in equal measure and their levels will vary from person to person.

Objective attempts to measure Gardner’s intelligences, interpersonal intelligence, for instance (the ability to understand the wishes and motivations of others) poses an enormous challenge. One possibility, and one which Gardner himself has employed when studying children, is to observe people who are challenged within one or more intelligences. This method is practiced within the corporate sector by large assessment centres. Candidates are grouped and then observed to determine how they tackle various tasks and relations. To arrive at applicable results, it is often necessary to carry out such observations over many consecutive days (or even weeks). It goes without saying that this procedure is particularly time-consuming as well as costly, which is why the procedure is normally confined to prospective appointees at very high managerial levels.

Best Predictor for future Job Performance

Recruiting and Selecting Candidates has one central goal: find the best candidate applicable for the job. What are the best resources on the market for that task? A insight into the validity of tools is an eye-opening experience within the field of HR.

One of the ways researchers determine if a recruitment method is good by assessing the criterion related validity of the tool. Criterion validity tells you how well the tool predicts future job performance. If the tool is capable of repeatedly predicting job performance, you will see high correlations between test and job performance, which is measured as a number between 0 and 1. If the validity is 0, there is absolutely no correlation between the tool used to assess a candidate and the future job performance of that candidate. Thus, indicating that there is no predictive value to the tool. In other words, it is purely coincidence if the candidate will be a good employee or not. On the other hand, if the validity is 1, there is an exact match between what we see from the assessment tool and the future performance. In reality, no assessment tool can predict job performance with 100% certainty, but the aim should be for the highest value.

We clearly see that the best tool to assess and select a candidate as a tool on its own is a GMA, otherwise known as a General Mental Ability Assessment. Kindly note, that another later study showed a slightly different result. To look into the data, kindly reach this article written by our Psychometrist.

The reason we can say that GMA is the most powerful single predictor of job performance is because the link between the two have been the interest of research for more than 100 years (Schmidt, Oh & Shaffer, 2016).

A lot of this research has been summarized using a meta-analytic approach. The renowned meta-analysis study by Schmidt and Hunter (1998) compared GMA to 18 other methods of assessing candidates and found that different methods and combinations of methods have very different validities for predicting future job performance. Some, such as the amount of education, have very low validity. Others, such as graphology (the study of handwriting), have virtually no validity; in other words, if you were to select a candidate based on the candidate’s handwriting it would be equivalent to hiring randomly.

Other methods, such as GMA tests, have very high validity. Schmidt and Hunter (1998) studied the combinations of methods and found that using GMA test and a structured interview combined showed a criterion validity of 0.63.

Other methods, such as GMA tests, have very high validity. Schmidt and Hunter (1998) studied the combinations of methods and found that using GMA test and a structured interview combined showed a criterion validity of 0.63.

Schmidt, Shaffer & Oh (2008) later concludes that GMA has even greater value when predicting job performance, than earlier studies show. And in 2016 they updated the meta-analysis from 1998 collecting data from 100 years of research. Their findings show a compelling strength in GMA tests (Schmidt, Oh & Shaffer, 2016).

Salgado et al., (2003) conducted a meta-analysis of the validity of GMA in 6 European countries, they found the validity to be in the range 0.56-0.68, similar findings to the American meta-studies, which show consistency of GMA’s validity across countries.

Le & Schmidt (2006) conduct a different meta-analysis to shed light on GMA validity across different job complexity levels. They found that even for the least complex profession the validity of GMA is 0.39 and an overwhelming 0.73 for the most complex professions. For professions of average complexity (where the largest number of workers are active), predictive validity is estimated to 0.66 (Le & Schmidt, 2006). The multitude of studies showing such a strong consensus in the high criterion validity between GMA and future job performance makes it difficult to overlook.

Why be interested in the research?

Research clearly shows that there are significant differences in the criterion validity of the different recruitment methods. So, what happens if we still overlook research when recruiting? To answer this question, we have switched the question around: How beneficial can it be if we listen to research, and use the best tool to predict job performance when assessing candidates?

To show the financial benefit of selecting the best recruitment method, we will use Utility Analysis - a set of procedures with roots in economics, finance, and psychology (Sturman, 2003). In this case we will use it as a tool for calculating the profitability of recruitment methods. By comparing two different recruitment methods we can show that even small differences in criterion validity can have a large economic impact.

To compare two recruitment methods using utility analysis, we need the criterion validity of each method and a recruitment scenario in which we want to compare the two methods.

Based on this information and the validity coefficients from Schmidt, Oh & Shaffer, 2016 (presented in figure 1) we can calculate the average improvement in performance in euros due to the selection device.

The criterion validity for the GMA-test is 0.65 and it is 0.58 for Structured Interview meaning there is a difference of 0.07. The last part means we needs to set up a hypothetical scenario.

If we put all the information into a Utility Analysis calculator or Utility Algorithm1, we can determine the financial benefit to be 58,992 €. If each GMA-test cost 50 euros, then the Return of Investment will be astonishing 590 %. Note that neither the total financial benefit nor the Return of Investment includes the cost of the current recruitment method. And still the result is a financial benefit of 58,992 € per year when employing 20 new people and the conditions are as mentioned above. This is the monetary difference of hiring people who are high performers and hiring people who are less likely to be high performers.

These results show how the seeming small difference of 0.07 can be transformed into a rather large financial difference in real recruitment methods. So, all in all, if we have the possibility of financial gain when hiring the right candidate, and improving our chances when recruiting by choosing the right assessment tools, why not use them?

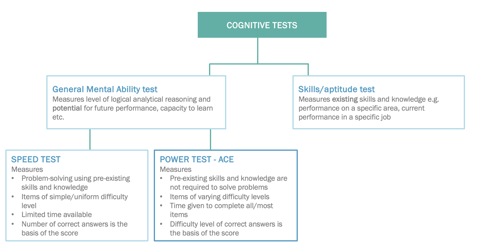

Speed vs Power Test

When we look at cognitive tests it’s necessary to differentiate and understand the fundamental differences between a speed and a power test and where our solutions fall between.

A power test takes into consideration what the maximum level of performance is. The questions in a power test range from easy and go until very complex. Generally, everybody completing the test will have enough time to do so. However, where the test differentiates is that those completing the test having high cognitive ability will get the more complex questions correct. The basis of the score is therefore based on the level of difficulty with correct answers.

A speed test, however, has questions of “uniform type” and a simple level of difficulty. If allowed with enough time, generally, most would be able to answer most of the questions correctly. However, in a speed test, time is limited and that means that the respondent either has to give quick answers (with the risk of a wrong answer) or leave some undone. The score is determined based on the number or amount of correct answers.

Most cognitive tests available on the market today are a mix of both tests (speed and power), which are also called “speeded power tests”. This means that the test is built up in a way that the question start off easy and get more and more challenging. However, a time aspect is also added, which means that it is hard to answer all the questions before time is up. This means that the difficulty of the questions may differ, but speed has a very strong influence on the score.

However, regarding speeded power tests many are of the opinion that being able to solve many problems fast is equal to being capable or able to solve more complex problems. Although a correlation between the two statements does exist, being fast at answering questions does not mean that the person is good at handling complexity.

Using speed as a measure of power can be difficult or challenging due to the practice effect. If a candidate has tried a similar test or questionnaire with similar questions, or if the candidate has a good testing strategy, that can increase the score, compared to people not using such tactics.

At Master International, we have developed the cognitive test, ACE. ACE measures and uses a balanced use of power and speed. This is done as liberal time is given to the respondent to answer the questions, meaning that time is not a stressful factor. In addition, it measures the level of difficulty when the respondent answers correct and additionally the speed of which the question was answered compared to a norm for each question. By measuring speed and power independently allows for accurate and detailed descriptions of speed and power used in logical and analytical reasoning.

Cognitive Test Build Up

Cognitive tests may be build up based on different layers. We can only speak from our own experience and knowledge. We work with three layers in our ACE Assessment:

• Verbal

• Spatial

• Numerical

For our CORE non-verbal assessment, we work only with the spatial layer.

Below you’ll fine examples which explain and demonstrate what a question for each layer might look like.

A question from the verbal section could look as follows:

In this item you will be provided with some information. Read this information carefully. Solve the item by ticking the box opposite the correct answers.

Thomas, Sarah, Max and Maria are 36, 39, 41, and 43 years old. Work out each persons’ age when you know that:

• Max is older than Maria and younger than Thomas.

• Sarah is younger than Max and older than Maria.

A similar question sound as follows:

Read the first pair of words (two words separated by a colon). Consider the relationship between the two words. Then read the first word in the next pair of words and select which response option should be the second word in this pair of words. The relationship between the second pair of words should correspond to the relationship between the first pair.

Cold : Warm

Black : ? 1. a) Glossy 2. b) Dark 3. c) White 4. d) Sun 5. e) Grey

A question from the number section could sound as follows: Read the information below carefully, and then answer the question. Your answer must be in round figures. Anne, Beatrice and Cecilia have divided $ 12.000 among them. Anne and Beatrice got an equal amount while Cecilia got twice as much as Anne and Beatrice together. How much money did Cecilia get?

Answer: $ ?